The topic of surge arrester failure is often discussed yet frequently misunderstood. While many assume arrester reliability can be characterized using familiar metrics such as Mean Time Between Failures (MTBF) or fixed service life expectancies, the reality is more complex. The variety of failure modes and the inherent difficulty in estimating the probability of failure (PoF) are often underestimated or neglected.

Surge arrester manufacturers are regularly asked to provide reliability metrics to support asset management decisions. MTBF is commonly requested or proposed as a standard measure, or alternatively, a generic service life estimate—typically 30 to 40 years under “normal conditions”—is provided without substantiated analysis.

Unfortunately, neither of these metrics properly reflects the actual reliability behavior of a surge arrester.

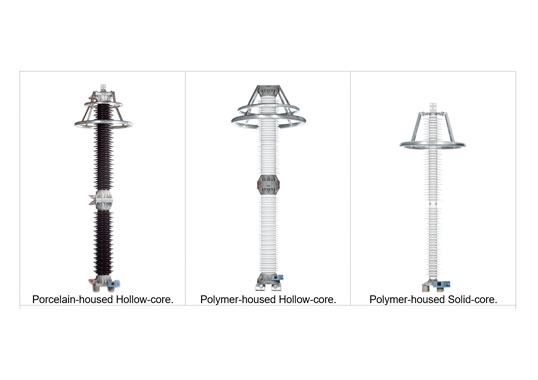

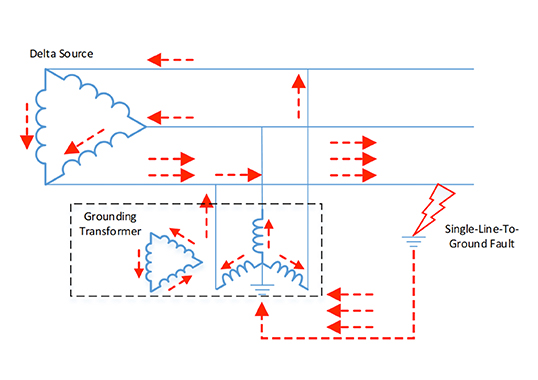

A surge arrester is a passive protection device, typically based on metal-oxide varistor (MOV) blocks. It does not fail in the same way as do relays, circuit breakers, UPS systems or power transformers. Unlike those components, arresters do not exhibit random or wear-out failures over time (in theory). Instead, failure occurs when the applied stress exceeds the arrester’s capability, often the result of accumulated energy, excessive temporary overvoltages or environmental degradation.

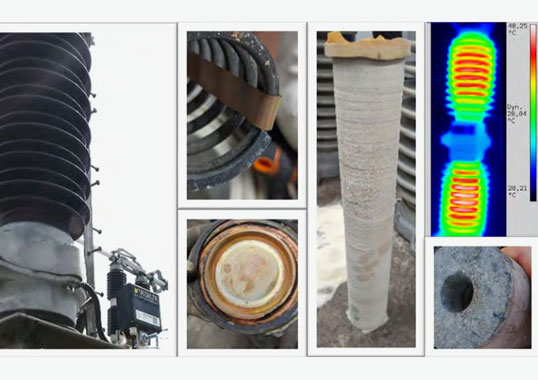

Importantly, surge arresters lack redundancy: if a single MOV block fails, it typically leads to thermal overload and eventually results in a short-circuit condition. In such cases, the arrester is completely damaged and must be replaced. There is no concept of partial failure or repair—a failed arrester cannot be fixed. This aspect is often overlooked by non-specialists, but it has significant implications for asset management and reliability modeling.

MTBF, which assumes a constant failure rate during the useful life phase of the ‘bathtub curve’ is therefore a misleading metric if applied to a surge arrester. For example, consider a utility operating 10,000 distribution-class arresters with 20 failures per year. This corresponds to an annual failure rate of 0.2%, or 2 failures per 1000 arresters per year. Expressed as MTBF, this would misleadingly imply a 500-year lifetime per arrester—a figure that has no practical meaning, since surge arresters fail due to specific stresses, not as the result of random time-based failure processes.

Service life expectancy (e.g. ‘30–40 years under normal conditions’) is somewhat more meaningful than MTBF but still carries important limitations. Such statements provide no statistical information on actual probability of failure and obscure the fact that arrester performance depends highly on application and exposure. In the field, arresters have been observed to fail after only a few weeks while others continue to operate reliably for over 40 years.

The most appropriate and useful reliability metric for surge arresters is annual probability of failure (PoF/year), i.e. expected failure rate under actual site-specific service conditions. This approach aligns with utility experience and field data compiled in CIGRÉ surveys. It also avoids false assumptions underlying time-based metrics such as MTBF.

Plan to participate at the upcoming 2025 INMR WORLD CONGRESS in Panama. Arrester expert, Florent Giraudet, will propose a reliability framework based on the stress–strength interference model, where failure occurs when actual electrical or environmental stress exceeds an arrester’s tested or expected strength. He will also discuss how, where applicable, this model can be refined over time using condition-based indicators, such as resistive leakage current or thermal diagnostics, particularly in substations where critical equipment is protected by station-class arresters. The objective of his technical lecture will be to apply this reliability framework to line surge arresters, with particular focus on externally gapped line arresters (EGLAs).